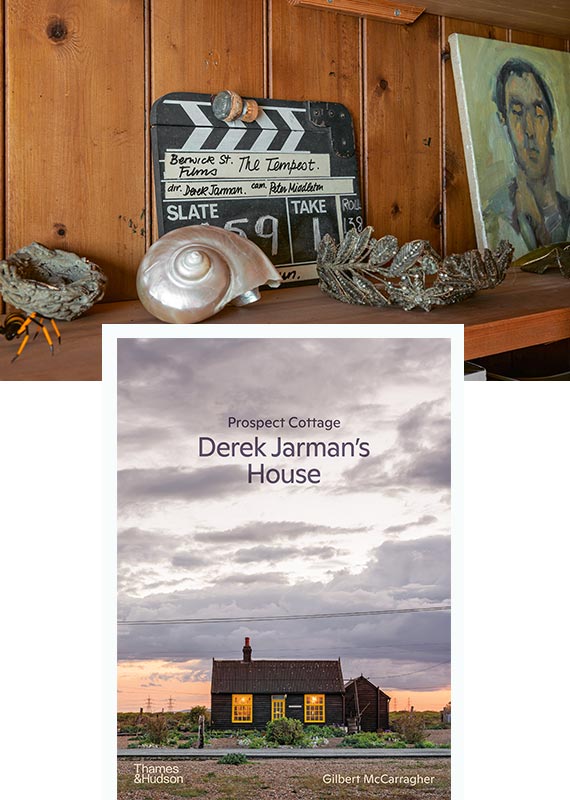

Enjoy an extract from beautiful new coffee table book, Prospect Cottage: Derek Jarman’s House

Anyone visiting Dungeness will know that Derek Jarman’s house is well worth a snoop for its striking surrounds alone – its canary yellow window frames are brilliantly incongruous against an often unforgiving sky, while its borderless poppy-filled gardens magically blend into the rugged coastal landscape. But few have seen inside the late seminal film maker’s sanctuary. Following his untimely death in 1994, the house was passed to Jarman’s long-time companion, Keith Collins, who did little to change the interiors – save for the addition of curtains to prevent visitors to the garden from peering inside. When Collins died suddenly in 2018, photographer Gilbert McCarragher, a friend and neighbour, was tasked with capturing this time capsule of an artist’s abode – arguably an artwork in its own right. The below is an extract from the book.

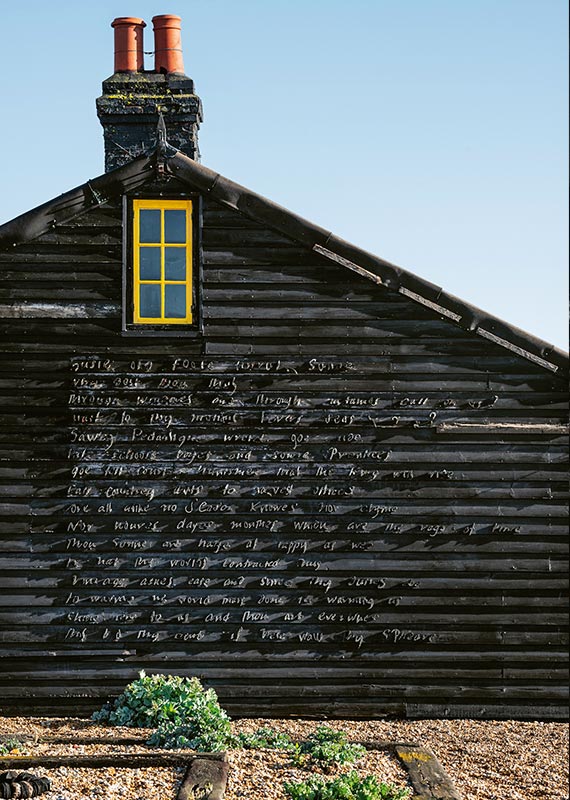

Excerpt from John Donne, The Sunne Rising (1633) on the southern wall of Prospect Cottage

Excerpt from John Donne, The Sunne Rising (1633) on the southern wall of Prospect Cottage

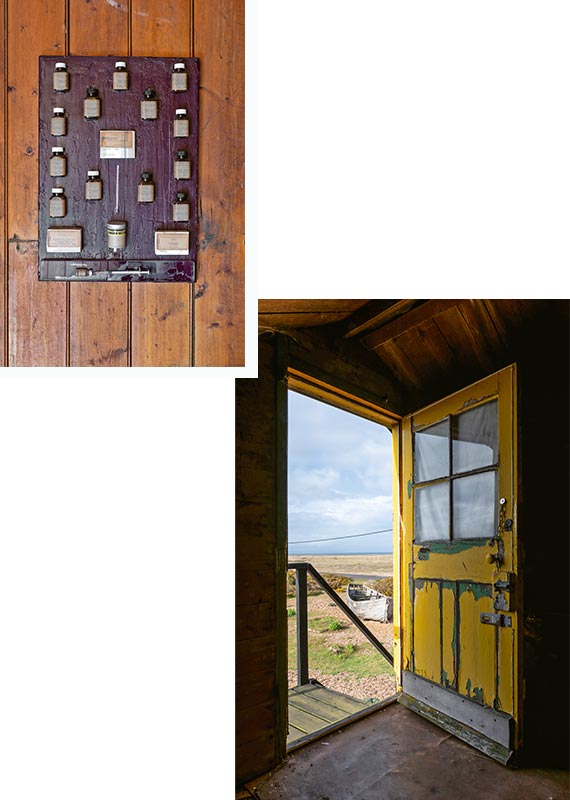

When you arrive at Prospect Cottage, you enter through an external door very much like that of the cottage’s other apertures in form. It is a vivid yellow colour and is made up of smaller panes of glass. Within one step of this, you encounter a second, internal door – wood-panelled, with a small window at head height, below which is a small mirror that reflects the views of the garden behind you.

It was important to keep one of these two doors closed, I learned while working at the house. Otherwise you very quickly found yourself face-to-face with a visitor from the garden who had strayed inside, expecting to have a look around.

Like much of Prospect, the walls and ceiling of the hallway are clad in timber tongue-and-groove. The hall is painted an unusual pale blue. Electric cabling runs over the walls and the ceiling, but the leads are knocked back with the same blue paint and therefore become near invisible.

Above the fireplace, a charcoal drawing of Keith by Robert Medley, made in 1989

Above the fireplace, a charcoal drawing of Keith by Robert Medley, made in 1989

On the left wall hang two rows of six black-and-white stills from Derek’s films. The opposite wall has a varied collection of framed posters and a small artwork by the British Pop artist Richard Hamilton. With the net curtains down, the presence of visitors to the garden throughout the day is more keenly felt.

Prospect Cottage originally consisted of four principal rooms, all roughly square and of equal size. The front room, followed by the studio, sits to the left. The Spring room, which is also known as the writing room, and then the bedroom, are to the right. While the house was extended under Derek and Keith’s watch, the four primary rooms remain at its heart.

Each of these rooms has a single window of the same size, divided into a grid of twenty panes of glass, five up and four across. The top two rows of each form a single awning that can be unhooked and opened outwards when fresh air is needed.

Through a weather-worn yellow door, the loft entrance is accessed via an external staircase. One Day’s Medication (1993) collates the daily dose of pills and injections required to treat the effects of the HIV virus described in Blue (1993)

Through a weather-worn yellow door, the loft entrance is accessed via an external staircase. One Day’s Medication (1993) collates the daily dose of pills and injections required to treat the effects of the HIV virus described in Blue (1993)

Solid oak floorboards span the original house from north to south, running from the Spring room through the hallway and into the front room in a series of almost unbroken lines that continue to the kitchen at the far end. If you look back along the hall towards the internal front door, any glimpse of the rising sun in its small window will appear very bright and focused, burning through the opening and illuminating the passageway entirely.

The floor in the hallway does not share the redness of the floors in the other rooms. As each board passes the threshold of a room, the change of colour is heralded by a soft gradient that dissolves from ecru into burnt umber. It was only after inspecting my photographs much later that I noticed this, having scratched my head for a while, wondering how a floorboard could look so distinct in the different rooms I had photographed it in, despite being the same long plank of wood.

Pictures and posters are stacked high, stored with the tools for maintaining Prospect

Pictures and posters are stacked high, stored with the tools for maintaining Prospect

I suspect the variation may have arisen from Keith’s approach to caring for Prospect after Derek’s death. He generally kept the doors to these four rooms of the cottage closed when not in use. This, I expect, focused his cleaning rituals on the most used areas of the house. Bearing a disproportionate amount of Keith’s labour, the hallway floorboards started to tell their own story.

Each door from the hallway to one of Prospect’s four primary rooms is also panelled in wood, the same as the internal entrance door, with a small glass window at head height, just big enough to frame a human head. My mother would have called such a window a ‘Widow’s Peep’. They allow the occupant to discreetly observe the comings and goings of the house without having to get involved in or be disturbed by them.

Most of these little windows are given their own identity by way of a small intervention: handwritten words or a fine drawing delicately etched in the glass, or simply an artefact suspended or sandwiched between its two panes. A small set of rosary beads made from rock salt hangs in the window of the door to the Spring room. Over time, the cross of the rosary has chipped and been worn down from repeated collisions with the panes, as it swings in a pendulum-like motion whenever the door is opened or closed. Small particles of salt from the cross have built up like snowflakes between the two sheets of glass in this door.

A Post-it note was at some point added to the bottom right corner of this window. ‘Do not slam the door’, it reads. I found this strange. Was the writer’s instruction not contrary to intentions? That religion might eventually erode away? Maybe I was reading too much into it.

Having paced out the house and come up with something of a plan for photographing it, I set about preparing the space. I began by taking down the net curtains from the windows of the four principal rooms. I gather these had been hung by Keith as a second line of defence for when the tiny note he had placed on the front door was overlooked.

Keith’s petite note informed visitors that they were welcome to enjoy the garden but asked them not to look through the windows. All too often it went unseen or was ignored, as people tried awkwardly to peer through the nets. I must confess, on long-past trips to Dungeness as an art student, to having pressed my nose against the windows in an attempt to do the same.

I had always been puzzled by the net curtains. They made the house feel cocooned and inward-looking. But I also understood Keith’s desire for privacy – curtains a necessary reality given the scrunching footfall that regularly echoed around the sculptural shingle garden outside. Derek had written about how Keith’s privacy had suffered as a result of living with him, and even when I was working at Prospect on my own, I felt the entire time as though I had company.

There was no space on the kitchen table for my camera gear when I arrived. Usually clear, it was piled high with unopened mail. Most of the accumulating mass was familiar to me as mail I also receive on the estate: bills; pizza brochures; double-glazing offers. I also spotted the elongated envelope that contained the calendar sent to residents each year by the neighbouring Dungeness power station.

The station’s annual calendar delivery was a running joke for many residents on the estate, and something Keith and I had laughed about on occasion. Its annual arrival was met with remarks that one of the twelve photographs of Dungeness wildlife it contained might be the last thing we would ever see. The same mocking laughter was directed at the box of iodine pills that came with the calendar, which it advised were to be taken in the event of a nuclear emergency. The utility of heeding the advice, should disaster strike, underpinned the dark jokes that followed.